The Loading Bay: Disused whisky warehouse finds new purpose as skate park, culture hub

What was once an empty whisky warehouse, where skaters would be shooed off by local authorities for riding on the building’s features, now serves as a 30,000 square-foot hub for the sport and urban culture in north Glasgow.

The Loading Bay, a project in Port Dundas run by Scottish Canals, is a large indoor skate park and culture hub that makes use of an outmoded spirits depot under ownership by the canal authority.

Phil Wilson, manager of The Loading Bay, said: “There's never been an indoor skate park of this kind in Glasgow. The overall reception has been really positive.”

Wilson, active in the skating scene of Glasgow for many years, said the park used to be exactly the type of place that he and his friends would be run off from when they were growing up.

The park, opened to riders and skaters in late November, held its official opening event on Saturday.

The event hosted park managers, representatives from Scottish Canals, an MSP, a city councillor and even an after-party hosted by Glasgow culture magazine The Skinny.

Wilson stated that the space draws big names in skating and BMX to the area and he views the culture surrounding the sport as more about camaraderie than competing against others.

“For most people who participate in these activities, it’s not so much about the competitive aspects of it. It’s about the community and it’s about having fun and egging each other on to accomplish your goals.”

He said: “For most people who participate in these activities, it’s not so much about the competitive aspects of it. It’s about the community and it’s about having fun and egging each other on to accomplish your goals. That’s what really keeps people in this. It’s about the way we all treat each other and boost each other up. It keeps things really positive.”

Bob Doris, MSP for Maryhill and Springburn as well as Glasgow City Councillor Robert Mooney of the Canal Ward were both in attendance to see how the local government is able to provide a space for young people in the skating community and others in their constituencies.

Doris said: “I think this is an amazing facility. I know this is a city-wide facility but it’s right on our doorstep of Maryhill and Springburn and it really benefits young people because it encourages them to participate in a really positive physical activity.”

With the Pinkston Watersports park nearby, Doris claimed that it will put Maryhill and Springburn on the map as “an action sports destination for the Glasgow area and beyond.”

TODDLER TESTING Coronavirus Scotland: Children under age of five can now get Covid-19 test as Scottish nurseries reopen

CHILDREN under five years old can be tested for Covid-19 from tomorrow as Scottish nurseries and childcare services emerge from lockdown.

The move was announced today by Nicola Sturgeon at the daily coronavirus briefing in Edinburgh.

Kids under five can get Covid-19 tests from tomorrow with Scotland's nurseries set to reopen (STOCK IMAGE)

The First Minister said: “This is a step which is designed to prevent families from having to self-isolate unnecessarily if young children develop symptoms.

"Something which we think is increasingly important as childcare resumes."

Previously, this age group was not allowed access to testing outside of clinical settings.

Interim Chief Medical Officer Gregor Smith added that this type of testing is important because of the reopening of childcare centres.

He said: “I would encourage anyone who has symptoms of Covid-19 or whose child has symptoms, to get a test immediately to help us suppress the spread of the virus.”

Dr. Smith said that children are very unlikely to have severe symptoms or to pass the virus on to adults, but stressed that they should still be tested if they show symptoms to avoid unnecessary isolation.

Adults and carers will be able to book a test for a child, Dr Smith said, by going to the NHS Inform website or calling 0800 028 2816.

It comes as no Scots died overnight from the virus for the fifth day in a row, meaning Scotland's death toll remains at 2,491.

There have been 22 new cases in the last 24 hours, the majority of them coming from Lanarkshire, where there has been an outbreak at a call centre.

Ms Sturgeon revealed “at least some” of the new cases announced today “are likely to be connected” to the outbreak at the Sitel centre in Motherwell, which is being used for NHS England's Test and Trace.

And Education Secretary John Swinney confirmed a final decision on reopening Scotland's schools in August will be made on July 30.

PHOTO ESSAY: Isle of Lewis - Stornoway

Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis is one of the main hubs of all island towns. Being the largest town on the largest Scottish Island, it’s home to the headquarters of the Harris Tweed Trust, the Western Isles Council and it’s the center of Gaelic culture on the islands.

AUDIO: An in-depth discussion with Jonathan Hopkins of the James Hutton Institute

During my time working on this project, I have relied heavily on one piece of academic research more than any other.

The issue of population decline on the Scottish Islands is not something that has received a lot of attention from the academic community or large media outlets.

The research conducted at The James Hutton Institute by Andrew Copus and Jonathan Hopkins is some of the most in-depth and comprehensive coverage that this issue will get.

I had the pleasure of spending some time speaking with Hopkins as we talked about his researcher and what it means for the future of the islands communities.

TRANSCRIPT:

Nick Haseloff 0:00

Yeah, so can you tell me a bit of your background and your work at the institute? Jonathan Hopkins 0:09 Sure. Yeah. I mean, I joined the I joined the Hudson Institute about seven years ago, I guess my backgrounds as a constitutive, geographer, and so previous to kind of physical geography but moving into moving into human geography, social statistics, I do a lot of data analysis related to demographics. Also GIS, spatial data analysis, indicators, well being and possible survey analysis as well. But the main kind of work I've been doing on this particular project is defining areas in Scotland which are sparsely populated, and so we're not looking so when you talk about sparse population that means poor access to people, it doesn't necessarily mean a low population density or country. Have remoteness from big cities or big towns, it kind of is a combination of those things. And so we've identified areas of Scotland which are sparsely populated. And actually, we've kind of just redone this again. So the publicly available reports which you'll have seen, we're going to be producing an updated revised version of that policy. And we've looked at the past population trends and use the kind of small area beta to project populations into the near near future in Excel 2530 years. And so that's been kind of that's been kind of my main, my main involvement in this work. I've also had a small, very small role in root silence revival projects, which was, which was probably no to do with this kind of anecdotal, anecdotal or qualitative evidence which have population change, which isn't reflected in the statistics. And that's kind of a major, a major kind of issue. I mean, the the most detailed population data comes out every 10 years and the census or 11 years because the one that was going to happen next year, it's been delayed a year. And so there isn't really any, any population information other than estimates in between. And so often you can have small areas, small villages, which have experiencing population growth and there's positivity in the community and there's a sense that people moving back which isn't picked up in the kind of statistics that I'm live in mainly involved in. So yeah, it's it's kind of something I've become increasingly aware of this, this need to accept that there is a there is a kind of spin quite negative picture of a future population in the islands. But that's not capturing every detail of what's happening in villages, and certain different parts of the island. Nick Haseloff 3:08 Yeah, so that's that's definitely something that because I initially had started my research with Ruth's findings and the eyelids or Bible project, because that is what got the most, most coverage in the media, ABC, BBC did a story on it, as well as quite a few other publications. But then you come to your research and look at the actual statistics and the data and look outside of that anecdotal area and you see a completely different picture. So that's, that's really what got me interested in the project and covering it in media in a way that necessarily wasn't covered before. So you've already touched on the dichotomy between those two different projects. Is there is there any similar Word of answer you have, can you put your finger on something that would lead to the difference in data? Jonathan Hopkins 4:09 Well, partly it could be it could be to do with scale. I mean, if you if you're in a small, a very small, you know, village in the in the highlands, or the islands somewhere, the population of that might just be five or six, it might just be a couple of houses with two families in it. Now, it might be that, you know, if you have another, if you have another family move in, if you have another house gets built, that's, you know, population growth of that small scale, and that could be pretty substantial and keeping that place going and then kind of maintaining, maintaining that place as a community. But if you look at the kind of if you look at kind of the statistics for data zones, and areas which are much bigger, you will kind of lose that. lose that degree of nuance, and I don't I mean, I guess I guess I'm biased a bit towards the quantity of beta because that's kind of what I've always I've, I've sort of been experienced in using, but But yeah, I mean, you know, there's definite sensitivity about, you know, you don't want to, you've got to accept that there are issues in the island population, you've got this this population aging. You have had the history of population loss and sparsely populated areas compared with more more accessible areas and areas around towns and cities. But yeah, you cannot. You can't ignore sort of kind of anecdotal among when they experience their everyday life. That's completely valid, valid view. And so yeah, it's in terms of deficiency can be a question of scale. It's small scale processes, which people experience but these kind of wider, wider areas. translate, they probably don't as much. So that's that's possibly one reason. Nick Haseloff 6:04 Yeah, one thing I noticed in your data, talking about the small, relatively small scale is you had, you had looked at projections of how much influx of immigration would need to be on the islands in order to reverse the change. And it wasn't much it was, I think, 458 or something like that on yours. And I mean, that's, that's less than what a ferry can handle. I mean, obviously, there needs to be housing and jobs and all that sort of stuff in these small communities. But for the for the numbers that have been projected, the solution to it seems rather small. Do you have anything you can say on that? Jonathan Hopkins 6:47 I mean, I mean, something. I mean, I'm did Andrew did that particular calculation, and we earned it actually, in the most recent one. We haven't. We haven't kind of reproduced that but but yeah, it's it's I mean, the thing that Because across all the time on the islands is the shortage of affordable housing. And then there's this kind of, I mean, you'll be aware of kind of the, you know, the Airbnb and people buy housing as an investment, and there isn't any affordable housing and, and so, yeah, it's it's kind of, it's kind of very, it's kind of very difficult to kind of report to get a movement of people back to the islands without without addressing burnout. And I'm, I'm not best placed to advise on the best way to do the mean, in some areas or meanings. I mean, as a country, we haven't built you know, the UK hasn't built affordable enough affordable housing for the last 40 odd years. So that's why they Nick Haseloff 7:48 It's definitely not being focused on these Island communities either. The affordable housing. Jonathan Hopkins 7:53 Exactly, exactly, exactly. But But yeah, I mean to to attract people to the islands. I mean, you know, you It's difficult. I guess it's difficult to to have that population movement without addressing the housing issue just because you hear it so often. I mean, you hear you hear this this issue of portable housing and available housing. And a lot of people, I think you might have seen the surveys that cheney have done on and on. And I forget exactly what it's called. I think it's about young people. I think, young people wanting to return and there's there is a desire of people to return to the islands to live there. But yeah, in order for that to happen, you need to get housing and you also need, you know, things like broadband and things like access to, you know, access to the sort of jobs that people want to do. So there's that there's a number of kind of issues, which are, it's not, it's not just housing, it's having economic, economic conditions where people can go back and solve what they want to do as well. So So yeah, I mean, it's it's it's, yeah, I mean, often when you do you do kind of demographic modeling and you work with economic data, it's easy to assume that, you know, people can they often assume that people didn't move around very easily. Well, in reality, there's there's a lot of values to this kind of this kind of migration, which people don't necessarily consider. Nick Haseloff 9:23 Going back to that modeling. I don't have a big background in human geography. What what type of modeling, have you relied on to make these projections? And how accurate Can we say they are? Has this modeling been used in the past in other communities and has it shown promise? And I'd know that you mentioned that there's another report coming out. Could you speak to that as well? Jonathan Hopkins 9:50 Yeah, I mean, I mean, for the I mean, for the I mean, we've got a couple of reports coming out one, it was kind of a reproduction of the kind of our sort of revived version of the report which I did with Andrew which is used on newer data and slightly slight changes, the other one's a bit more experimental, which, which is perhaps a bit less easy to explain. But the population projections is kind of a method that's been applied to other areas. You look at the current population structure. So you have details of the number of people in sparsely populated areas who are five year age groups, men and women, and then you apply birth rates and birthrate prediction and so you know, how many people are being born, you know, you apply mortality rates. So, you know, which are specific to different age groups and gender groups and different locations. And you also apply migration assumptions and that's that's the tricky bit because migration is the hardest is the thing that there's most uncertainty over birth rates and death rates tend to be fairly slow moving in time, but migrations the so what we did for that was we used recent migration assumptions, which are based on recent migration data. So it's kind of assuming a status quo assumes that each migration will be similar to that in the recent past, I guess. And through this use of, you know, small population data and population structures, you can then apply, you could then get a five year periods out to 2043. I think, the population structures for those years and you can then get, and then you can get kind of the statistics from that. So it's kind of an established, it's kind of an established method. We've obviously applied to quite small areas, using small area data. There's a lot of assumptions in that kind of work. Which I think we've acknowledged. But it's kind of wait, I think we've done a decent job with the data that we've we've got available. You can, you know, I mean, you can never, you can never have too much faith in modeling. Because as you know, as we, as we all know, how does now you can get these completely unforeseen events which can change everything. But yeah, Nick Haseloff 12:23 How close is the new data that you've been working on to what you had modeled in that report? Jonathan Hopkins 12:29 It's pretty, it's pretty similar. I'm just trying off the off the top of my head. They this new report, which is updated projections, it's a slightly different time period. So I think in the first report, Andrew use 2011 data and it went to 2046. Because there's population data in this new report available for 2018. We've done it to a slightly different period. So it's now projected in 2043, I think, and I think we get similar results we get pretty soon Similar trends happen actually something I actually haven't done this is to to compare across the two, but you tend to see, you tend to come in to see similar things. So the regions where some of the kind of violent weakens in the West tend to have the most negative population changes. And I think Shetland Islands spot popular parts of the Shetland Islands, I'm not sure they have the most positive to populating trends. And again, I mean, I guess something I mean, when we're doing these projections, you're reporting statistics for different regions and obviously within that region, while the population projection for the whole region might be negative, there could be bits, which are positive, there could be smaller parts of it which are positive. And if you look at the reports, which national records of Scotland to produce looking at the working age population, something that But to some of the comes out of them is the whole of Scotland is going to have a slight decline in the working age population by sort of 2043. I think. So, you know, demographic issues aren't just affecting sparsely populated areas, they're affecting all parts of Scotland to some to some degree, I guess. Nick Haseloff 14:19 I don't know if you know, off the top of your head, what percentage of the area of these islands is considered sparsely populated? Jonathan Hopkins 14:27 Well, that's, that's a tricky. One. Isn't that Oh, I've got them. I've got map, which I don't know if I can. I don't have I don't have available. But for instance, if you take if you take, say the islands, which is sparsely populated, isn't the kind of you know, there's a mainland of Army and you've got luik, the main town and you've got the mainland area, that bit of it is actually not sparsely populated. The popular bit important is kind of Outlying Islands and the kinds of edges of mainland Island I think So because there's something that we've picked up on is there's kind of a contrast between the kind of Central towns and Island areas, so stone away. And Kirkwall. These kinds of areas, you know, tend to be kind of key kind of hub towns for the islands. And so it's a kind of maintain population economic activity in a different context, the more remote parts of the island, so that's why we think it's useful to have it's useful to have that back kind of split. Nick Haseloff 15:35 So you feel that these Kirkwall, Stornoway, those sort of hub towns, you don't feel that they will see the same amount of decline as the spark sparsely populated areas. You don't feel that it's reflected. Jonathan Hopkins 15:49 I touched on serasa I'd have to double check on the kind of results for that, but they've, they've got kind of advantages which the more remote parts of galleries don't have, you've got this agglomeration. of service such as an economic activity and people and that kind of support population, that kind of agglomeration you just don't have in the mall kind of areas. So the theory would suggest that, yes, the remote areas are going to have that threatened more by that kind of the population, which is a horrible word. I really don't like the term the population. It's a bit of a, you know, it's just not a nice, not a nice to, but that but yeah, maintain population, although it's going to be it's going to be harder, just because you don't you don't have access to that kindof agglomeration. Nick Haseloff 16:37 Are you aware at all of the Isle of Rome and the Eco homes that they're building there? Jonathan Hopkins 16:44 I'm not No, I mean, I'm aware of Rome, but I mean, it's, I mean, it's, I know that there's groups in the islands who are kind of kind of doing similar thing. Please tell me more about that sounds sounds very interesting. Nick Haseloff 16:57 Yeah. So I think their population hovers between 30 and 40. And they're in the process. They're hoping to finish next month that they're building for eco homes. So they're all powered off the grid. No, no traditional sewage, that sort of stuff. But they're, they're hosting applications for people to move there. So they're hoping to almost double their population, hopefully. Jonathan Hopkins 17:24 So that's right now that's the recipe that's really, really interesting remembering. Yeah, I mean, how big is how big is Rome? I can't remember. It's. Nick Haseloff 17:33 Yeah, it's very small, though. Jonathan Hopkins 17:35 Yeah, but I mean, I guess I guess the polling population these remote islands. Yeah, I mean, I mean, what what do you know what the kind of, you know, are they are they are there jobs that people are going to be doing on the island or Nick Haseloff 17:49 the main thing is, there's there's aren't a ton of jobs there. Most of it has to do with tourism, and obviously, most of its seasonal. So it's going to be interesting to see what their criteria is we're getting people on the islands. I think they're hoping for most people to have remote jobs that they can work from. Jonathan Hopkins 18:06 Yeah, man. I mean, that's really interesting, because it's kind of, you know, you know, I mean, time we've all become more used to home working than than ever before. It's kind of Yeah, mate, enabling people to kind of participate in economic activity sort of wherever, wherever that happens, I guess. Yeah, that's very important for places like that. But now that I've not I've not heard about, but I think there's a few similar communities, but it's not something that I'm very, I mean, I'm very much sort of quantitative data, yeah, data person. And an all the time you can kind of you kind of learn the value of what you might pass as anecdotal evidence, as you know, it's, you learn about the values of people's experience and all of the colleagues or with a more called seven. So I'm involved in, I'm involved in are involved in this kind of interviews, focus groups and shops and things like that good. Yeah. And often you can have these two sets of data which, you know, present very, very different, different pictures of both, but both can be validated that so it's something that I suddenly I know about. Nick Haseloff 19:19 Alright, thank you so much. Hope you have a great rest of your day. Jonathan Hopkins 19:21 You too. Nice sweet too. Thank you. Bye. Cheers. Bye Transcribed by https://otter.ai

A remote Scottish island is offering up four homes to outsiders in an effort to help populate the island.

The ‘eco homes’ are up for grabs on the Isle of Rum in the Inner Hebrides, which has a population of around 30-40 people.

Newcomers will have to fill in an application form for one of the £450-a-month houses located just outside Kinloch - the only village on the island.

Rum is 30 miles from the Scottish mainland and accessed via ferry from Mallaig near Skye.

The islands website reads: “These state of the art, two-bedroom homes sit on the edge of the village of Kinloch with clear sweeping views up to the majestic Rum Cuillin.

“These houses remove a major barrier to accessing the many working opportunities on the island.

“The homes have been made possible with major support from the Scottish Government's Rural and Islands Housing Fund.”

The island is a National Nature Reserve and is roamed by wild red deer, goats and cattle.

The off-grid homes are powered via a hydro system and there is a compost system for disposing of waste.

They boast incredible views away from the hustle and bustle of the city plus clean living.

Construction of the houses has been delayed due to coronavirus, but the trust plan to have them ready for September.

Local resident Lesley Watt said: "We have a population of around 32 people, including six children.

"With only one child in nursery and two in our primary school we need more families to fill our school as well as to be the next generation of islanders."

The main industries on the island include fish farming, food production, childcare and marine and mountain tourism.

The homes are being offered by the Isle of Rum Community Trust and interested tenants can find out more here.

Study shows that sparsely populated areas of Scottish Islands could diminish by up to 25 percent

A study published earlier this year shows further evidence of a sinking population in most Scottish island communities.

The research, conducted by the James Hutton Institute, predicts that the population of the sparsely populated areas of these islands will diminish by up to 25 percent by 2046.

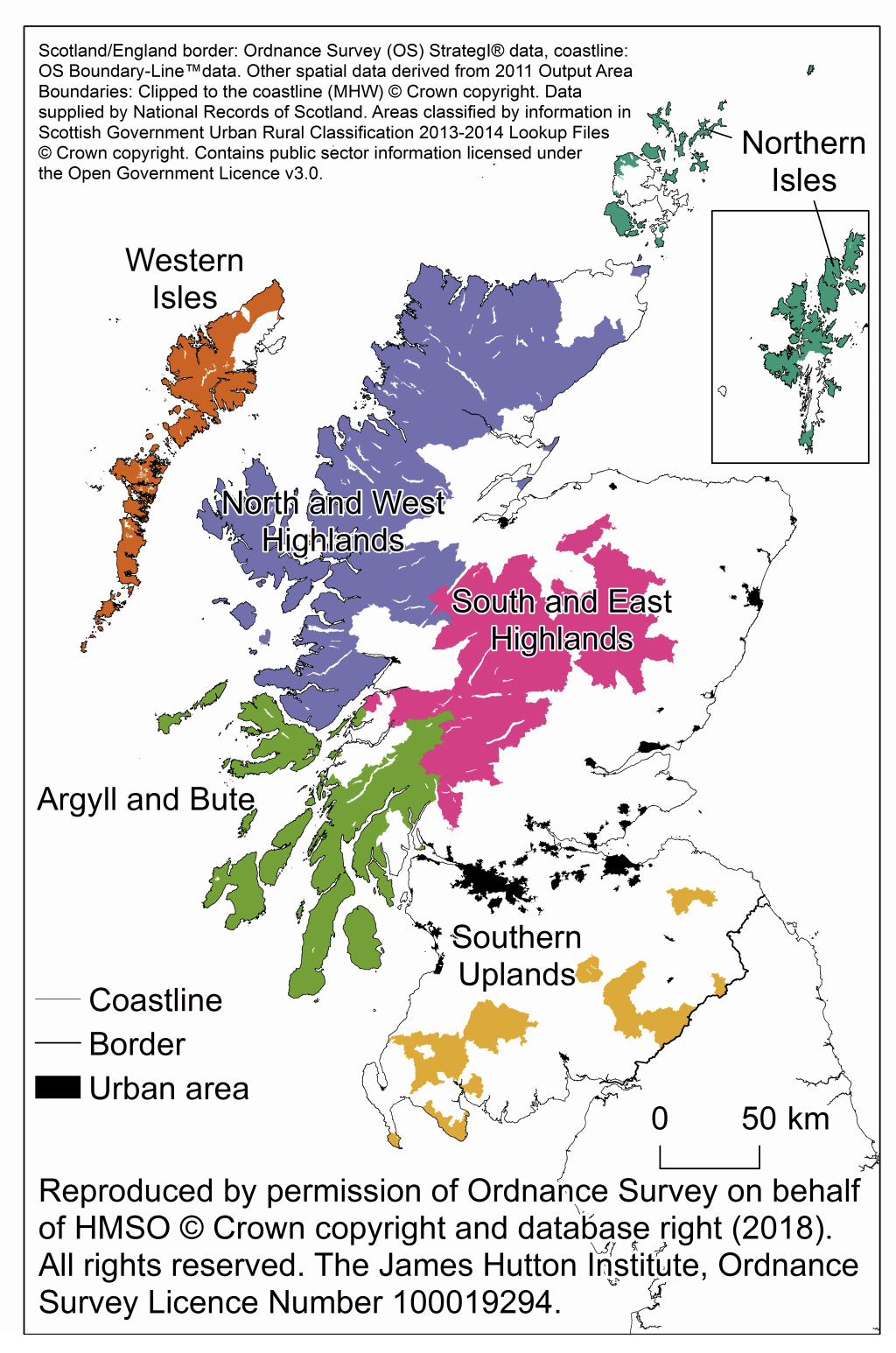

Researchers Andrew Copus and Jonathan Hopkins looked at data from population census records from 1991, 2001 and 2011 as well as a number of other indicators to formulate their projections.

Hopkins said: “We used a number of statistical models to formulate this data.

“The models we used have been tried and tested on a number of other similar projects and have proved to be very reliable.”

The projections are based on estimated population numbers that are broken up into five-year chunks which start in 2011 and end in 2046

Communities such as the Western Isles and Argyll and Bute will be the most severely affected according to the study.

Projections show that these two areas are expected to lose up to 30 percent of the number of residents from the 2011 census.

Hopkins said: “The main reason for these lower population figures is the lack of affordable housing on the islands.

“That, coupled with the limited job opportunities on the islands means that it’s hard for people to have a reason to move to the islands.

Copus and Hopkins used indicators such as population estimates from National Record Scotland to support their projections.

Hopkins said one of the biggest detriments to accurately reporting on these statistics is that there is a lack of data. The official census records only occur once every ten years and the census for 2021 has been pushed back due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Hopkins said: “I’ve come at the issue from a very quantitative perspective and when you look at only the numbers, it shows a very negative outlook for these island communities.

“But in the meantime, my colleagues here at The James Hutton Institute have heard many stories of anecdotal evidence of population resurgence in the exact same areas where our research is showing a decline.

“It’s easy to sit here and dismiss this evidence as simply ‘anecdotal’ but as a human geographer, we have to pay attention to the stories of the people we’re studying as well.

“The difference between the stories we’re hearing and the figures we’re looking at means that this has been a very interesting topic to cover and we’re interested to see how the future census numbers change our research,”

The anecdotal evidence that Hopkins is referring to comes from the Islands Revival Project. Another researcher at the Hutton Institute, Ruth Wilson, led the project.

The purpose of the project was to gather qualitative evidence of population resurgence on the islands by getting the community involved through sharing written stories on a website that the study had set up.

The site hosts writings from communities all across the islands which highlight positive topics of population increase and look at projects within these communities that aim to battle the problem of population decline.

The project was part of a collaboration by The James Hutton Institute, the Scottish Government and Scotland’s Rural College.

Copus has since left the institute, but Hopkins said he is continuing the research and plans to release new figures which analyze much newer data from 2018 and project the population figures out to 2043.

One of the most interesting factors of the research according to Hopkins, is that Copus was able to use data from the projections to predict the number of people that would need to join the population on the islands in order for the declination to subside.

Their calculations found that just 1,300 people would need to move to the sparsely populated areas of the islands in order to counteract the issue.

Hopkins said: “The real issue isn’t necessarily the number of people we need to get to the islands, but rather where they’re going to live and work once they get there.”

The James Hutton Institute plans to release updated statistics on this issue later this year.

Young couple retreats back to their Scottish island roots amidst global pandemic

When Lewis MacMillan and Lois Mackenzie met as teenagers, they had lived their whole lives in the small isolated community on the Isle of Lewis.

Lewis and Lois

After moving to the mainland for university and completing their postgraduate degrees in Glasgow, they said they still value the community and natural wonder that island life provides.

The couple met on the island at church and have been together for eight years. The two got engaged on Bosta Beach in the north of Lewis last summer.

Lois said: “Some of my earliest memories of growing up on Lewis are the long summer days I would spend on the beach in front of our home.

“When explaining island life to my friends on the mainland, I tell them about the island’s beauty, but also about how traditional and different life is on Lewis.”

The couple retreated back to their summer jobs on the island just in time to dodge having to spend the entirety of the coronavirus lockdown in the city.

Lois said: “I’ve had a set summer job here since before I moved to uni which I love. It’s in the middle of nowhere and near so many beautiful beaches and walks so I had always planned to come back for this summer.

“It just happened to work out this year that the virus hit and back home on Lewis was the right place to be.”

“There just aren’t a lot of jobs available in the public sector as there really isn’t a whole lot of industry on the island. It’s hard for people to find work after they come back from school.”

Their story serves as a tell-tale for what many young adults from the islands are experiencing when they graduate from uni.

Lois said: “There just aren’t a lot of jobs available in the public sector as there really isn’t a whole lot of industry on the island. It’s hard for people to find work after they come back from school.”

According to Jonathan Hopkins of the Hutton institute, many studies show that the population of working-class aged individuals is on the downturn in all of Scotland and this statistic is likely to affect island communities greatly.

Jonathan said: “These islands are already struggling to keep this demographic in their communities.

“With the open availability of education, many of the young adults leave the islands to go to university and don’t come back as they don’t see much opportunity for job growth.”

Lois said that she and Lewis are not planning to live on the island in the long term.

She said: “Lois is a business major and I have a background in English and Journalism.

“There just really aren’t a whole lot of jobs besides what you find in the public sector that would really suit what we want to do with our careers.”

VIDEO ESSAY: Isle of Bute

During my time on these islands, studying them and getting to know the people that call them home, I have come across the same sentiment from any one who has spent a deal of time there. That sentiment is that the islands are a calm, peaceful and tranquil place and the lifestyle there is a unique experience that can only be realized once you spend a time on the islands. Through my travels on multiple islands, I have come to realize that each island has its own personality. Island life has its constants which can be found on each island, but every island offers something different for those looking to find it.

The small Island of Bute is located in the Firth of Clyde, just off the coast of the mainland. It’s one town Rothesay is home to the bulk of the island’s 6,500 residents. The 13-mile loop road circumnavigating the island makes it easy to get around and see all of the beauty the island has to offer.

The video below is an attempt to capture the tranquility and peacefulness that island life provides and allow a glimpse of what most mainlanders don’t get to see.

English entrepreneur leaves city behind for tranquil island life

When Englishman Matt Armstrong-Ford left Eastbourne for the Isle of Bute with his partner Emily before lockdown, they did so with the intention of saying goodbye to a grandmother, but ended up realizing they had no intention of going back.

Matt Armstong-Ford

Matt, who owns an African safari travel business, moved with his partner to Kilchattan Bay, a tiny community on the Isle of Bute after Emily’s grandmother passed.

He said: “We came up to visit her before she died. She died the day before lockdown so we effectively ended up being ‘stuck’ in Scotland.

“We decided that this place has everything we are looking for to build a life and a home. We’re now in the process of buying the house she lived in. Given that we both travel a lot for work. It is a perfect place to come back to and enjoy the quietness and calm of island life.”

Bute’s population sits below 6,500 residents currently and the tiny village of Kilchattan Bay is home to just a handful of households.

Matt said that living in this remote island village poses a number of positive differences to the normal city life on the mainland that he has been used to.

“The pace of life is a lot slower on the Island. There’s no traffic, except the odd cow or sheep on the road.”

He said: “The pace of life is a lot slower on the Island. There’s no traffic, except the odd cow or sheep on the road. No noise pollution. Overall, just a general sense of calm and community that doesn't seem to exist in most towns and cities on the mainland.

After living in Tanzania & Zambia for three years running safari lodges and guiding guests on safari expeditions, Matt moved back home to England to start his own African safari travel business.

He runs his company, Armstrong Safaris, solely and takes clients on breath-taking tours of Africa’s more remote areas.

Boathouse on Kilchattan Bay

Nick Haseloff

He said: “We plan to split our time between Africa and the island. Six months here and six months there.”

He said that Emily is an artist and ‘the pace of life and quietness on the island gives her the opportunity to paint without distraction.”

Matt and his partner are lucky in that their careers allow them to work from a remote location.

Researchers from the James Hutton institute attribute lack of job opportunities on the Scottish Islands as one of the main factors of population decline in these communities.

Researcher Jonathan Hopkins said: “There’s a real problem with affordable housing too. There isn’t a lot of job availability in these communities, but even if there were, those new workers would have a lot of difficulty finding a place to live.”

The research conducted by the James Hutton institute projects that Bute may be one of the communities worst impacted by the problem of population decline.

They expect the island to lose up to 30% of its population represented in the 2011 census numbers.

Hopkins stressed that anecdotal evidence of resurgence such as Matt’s story paint a contrasting picture however.

Hopkins said: “It’s easy to discount these stories as simply being ‘anecdotal,’ but the truth is that they relay information in a different manner to the negative quantitative outlook that the population modelling shows.

“These people’s stories are just as important and give us information that we can’t get from just looking at the numbers.”

VIDEO: An introduction to the topic

TRANSCRIPT: Looking at a map of Scotland, the northernmost country in the United Kingdom, it’s easiest to pick out the large population centers like Glasgow and Edinburgh, but there is still a large swath of the Scottish population that lives north of this line, often called the Highland Boundary, it separates the area known as the Scottish Highlands from the rest of the country. Mostly known best for things like kilts and clans and haggis and outlander, there’s a lot more going on in the highlands of Scotland than what you hear about in the cuurent zeitgeist. One quintessential part of highland culture and heritage that isn’t necessarily well-known outside of Scotland is island life. Away from the population centers of the south, Scotland is home to over 900 islands. Ranging in size from the smallest island Eilean Donan, to the largest island, the Isle of Lewis and Harris. 94 of the Scottish islands are currently inhabited and some, such as Lewis and Harris and Orkney, are home to thousands of residents. But over the past decades, these islands have struggled to keep their population afloat. New studies estimate that the sparsely populated areas of the islands could diminish by up to 25% by 2046. And even the more populated towns like Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis and Kirkwall on Orkney are expected to join this downward trend. Many experts attribute this population decline to a number of factors: including a disparate birth and death rate, economic influences and higher education and job opportunities on the mainland. This is a story with a lot of tiny moving parts and there are some big plans in the works to fix these issues. Over the next several weeks, this site will host a journalistic series which will dive into the issue of population decline on Scottish islands and will look at anecdotal evidence of resurgence. We’ll look at specific islands as case studies for this phenomenon and study the data so that we can formulate a clearer picture. We’ll also look at the steps the Scottish government is taking in the forms of the islands act and the national islands plan. You’ll read and hear interviews from experts on the subject as well as locals who have spent their entire lives on the islands. All of this in an effort to bring light to this complicated issue.

Business closings due to pandemic impact much needed tourism industry on Stornoway

Located on the Isle of Lewis and Harris, Stornoway, like many other island settlements, has seen a decline in population over the past decades. A dip that residents hoped would be surmounted by a flourishing tourism industry.

Because of a lack of incoming visitors caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, that industry has taken a tough hit from the impacts of the nationwide lockdown.

The Harris and Lewis Smokehouse is one of two restaurants on the island which closed due to difficulties resulting from COVID-19,

Nick Haseloff

“There’s a great reticence on the island at the moment to have any tourists at all.”

“Well, I would say there's a great reticence on the island at the moment to have any tourists at all,” Malcolm MacDonald, Chair of the Stornoway Historical Society said. “We were lucky to only have seven or eight cases on the island. And they all retreated at home. There were no deaths. And I think there's a fear that once you open the floodgates, that COVID-19 will enter the islands.”

According to Ian McKinnon, Chief Executive of Outer Hebrides Tourism, many bed and breakfasts and restaurants on the island have decided to stay closed for the rest of the season and two restaurants on the islands have had to close their doors permanently.

“The tourism industry here isn’t like what you’re used to on the mainland,” said McKinnon. “Most of these restaurants and hotels are run by one or two people.”

According to McKinnon, the tourism industry makes up 10-15% of Lewis and Harris’ income, and the impacts of the lack of revenue could take the island years to recover from.

That percentage of income accounts for many jobs on the island that have taken the place of industries lost over recent years.

“It’s quite important for people on the islands to be able to supplement their income,” McKinnon said. “You’ll have people that work most of the time as teachers or in the shops and they’ll pick up a second job to make more money. It’s quite common for people on the island to have two or three jobs.”

Studies by the James Hutton Institute and the Scottish Government show that Comhairle nan Eilean Siar (the Western Isles Council), for which Stornoway is the home of, is expected to lose up to 20 percent of its working age population by 2041.

Many of these younger island residents leave for the mainland to attend university, and often many of them do not return.

“Well, one of the main reasons people leave the island is employment opportunities.” MacDonald said. “There are a high percentage of pupils, you know, who go on to further

Crowd fills Madison County board meeting to discuss proposed asphalt plant

MARSHALL - Dozens of opponents of a proposed asphalt plant urged the Madison County Board of Commissioners to consider a moratorium on industrial zoning permits at the board's Tuesday meeting.

About 300 people on both sides of the issue crowded the meeting at the A-B Tech Madison campus. The main auditorium quickly filled to capacity; others were asked to watch a video simulcast shown in an adjacent room.

Donnie Reed, owner and operator of French Broad Paving adresses the Madison County Board of Commissioners Feb. 12. Reed's company intends to build an asphalt plant in Madison County and the proposal sparked a long discussion amongst the public.

The asphalt plant, which would occupy a leased space at McCrary Stone Service quarry, is a project by French Broad Paving, a Madison County-based paving company owned and operated by Donnie and T.J. Reed. The Reeds submitted applications for zoning permits earlier this month so they could move forward with the process of building the facility.

"I started this company in 1997, with my son and a small loan," Donnie Reed said at the meeting. "Now, I am trying to grow that business further by constructing an asphalt plant here in Madison County."

French Broad Paving employees and family members showed support by wearing bright yellow shirts and hoodies brandishing the company's logo, while those opposing the plant held signs citing potential risks to residents' health and tax income from tourism and wore buttons with "No Asphalt Plant" written on them.

Asphalt plant wasn't on the agenda

Donnie Hall, Madison County's attorney, cautioned before the public comment section of the meeting that the Board of Commissioners had no plans to talk about the proposed plant as commissioners had no influence on the zoning process as a result of county ordinances adopted 10 years prior.

"This is not the proper forum for that process," Hall said. "Because these are not the folks making that decision."

Hall stressed that the zoning proposal already made it to the county's zoning board and any opponents of the proposal would need to attend the quasi-judicial hearing, which the Madison County Board of Adjustments holds if they wanted to provide evidence in an attempt to negate or support it.

"This forum was created so that people in the community could let it be known about issues affecting them," Hall said.

Out of the crowd, 30 people voiced their opinion either for or against the construction of the plant. Each member of the public was given three minutes to speak their mind.

Janet Spivey and Ellie Pinkham hold signs protesting the proposed asphalt plant during the Board of Commissioners meeting. The main lecture hall at the A-B Tech Madison campus was filled to capacity and others wishing to view the meeting were put into an overflow room down the hall.

Air quality raised as a concern

Along with concerns about environmental pollution, opponents cited lowered property values and a risk to the tourism industry as their main qualms with the facility.

"I live half a mile from the proposed location," said Marshall resident Emily Sontag. "I spoke with people that live near a similar plant in Weaverville and from what I've heard, I'm worried about a plant like this being built so close to my home."

Sontag said she heard reports from Weaverville residents of year-round odors from the plant, fumes that would sting residents eyes and constant noise pollution from trucks and heavy machinery operating in the area.

Members of the public gather at the A-B Tech Madison campus Feb. 12 to attend the Madison County Board of Commissioners meeting. 30 people use the meeting's public comment section to discuss the effects of a propsed asphalt plant just outside of downtown Marshall.

French Broad Paving invited Mona Brandon, a senior environmental scientist for TRC Environmental, to speak about the proposed plant and the predicted impacts it could have on the environment.

"The North Carolina legislature has set strict guidelines outlining the allowable amount of pollution that asphalt plants such as the one French Broad Paving is proposing should be allowed to produce at any given time," Brandon said. "The estimates that factor into the approval process for these types of facilities assume that the plant would be running 24/7. The estimated air quality of the emissions of this proposed plant fall well within those regulations."

A request for a moratorium

Ellen Holmes Pearson, a Marshall resident and member of Sustainable Madison, was one of the first of many opposing the plant. She presented the idea of a temporary moratorium on industrial zoning permits so the county's zoning board could take more time to examine factors surrounding safety and environmental impact of all industrial zoning permit requests before granting permits like the ones requested by French Broad Paving.

"We suggest that we create a Madison County Environmental Council to deal with these sorts of issues," Holmes Pearson said. "There are still yet too many unknowns to move forward with this process."

None of the members of the Board of Commissioners made any statements regarding the asphalt plant or any other issues spoken about during the public comment section of the meeting.

The application for the asphalt plant now must go through the zoning procedures and the Board of Adjustments before it is approved and building of the facility can commence.

School lunch programs becoming more essential for North Carolina families

Child nutrition assistant Denise Ballentine passes out lunches to pre-K students at Blue Ridge School in Cashiers. The Jackson County school is one of the few in the state with a public pre-K program. Since the school also qualifies for a blanket free-lunch program for all attendees, pre-K students benefit from the same free lunch as the rest of the children.

A majority of North Carolina parents lack the financial resources to provide school lunches for their children without assistance, according to federal data, a situation that has worsened in recent years.

Most children in North Carolina participate in the National School Lunch Program, which provides free and reduced-price school lunches to families facing financial hardship. In the 2016-17 school year, 59.8 percent of public school students in the state received lunches through this program, according to the N.C. Department of Public Instruction. That’s 10 percentage points higher than the level of participation a decade earlier.

Projections from North Carolina public school administrators for the 2018-19 school year show that a high percentage of students will continue to benefit from the program, provided they apply, which they must do each year.

While some parents make a conscious decision not to participate in the lunch program despite being eligible, school nutrition experts across the state told Carolina Public Press that lack of knowledge about the program or forgetting to reapply are the biggest reasons that children miss out on the meals.

“One of the biggest problems I’ve seen is that parents don’t know that they have to reapply every year for the free and reduced lunch program,” said Rebecca Bryan, an administrator with Child Nutrition Services for the Wake County Public School System.

The school district in Wake County is the largest in the state and their percentage of students enrolled in the program largely reflects the same ratio as the state as a whole. All parents of students in the district are sent information at the beginning of every school year about how to apply for free or reduced school lunches.

“It’s really easy to apply online,” Bryan said. “If they don’t apply before the start of the school year, their child only receives a couple of days worth of free lunch before they’re served alternative meals mainly consisting of just fruits and vegetables. I really urge all of the parents that need it to apply.”

Second-grade assistant Kari Reed keeps the eating area clean as students eat their lunch at Blue Ridge School in Cashiers in Jackson County.

According to Jeff Wyant, assistant principal at Blue Ridge School, a public pre-K through early college school located in Cashiers in Jackson County, the breakfasts and lunches that some students receive at the small rural school are the only meals they will eat that day.

“The free and reduced lunch program we provide is really beneficial to the people of our community,” Wyant said. “We’re what you would call a high-needs school. A lot of the jobs in this area are seasonal and families can’t afford to pay for school lunches every day.”

Blue Ridge School is registered under the Community Eligibility Provision program provided by the federal government. Their enrollment in this program means that a high enough percentage of the school’s students would have qualified for free or reduced lunch that the school is issued a blanket grant which ensures none of their students need to pay for school lunches.

“We only have around 400 students and the CEP program just makes it easier on everyone,” said Tina Coggins, child nutrition manager for Blue Ridge School. “We’ve been a part of the program for four years and we’ll reapply after it runs out at the end of this year.”

While Blue Ridge School is one of only two schools that qualify for the CEP program in the Jackson County School District, other districts in the state apply as a whole so that all of their schools can benefit.

“It really creates less burden as a district,” said Amy Stanley, director of nutrition services at Bladen County Schools and president of the School Nutrition Association of North Carolina. “When all of our schools qualify under the district, we gain a lot of benefits. There’s no parents need to fill out applications, there’s no stigma surrounding getting a free lunch for the students and there’s no unpaid charges.”

According to Stanley, despite the school lunches that students in the Bladen County Schools district receive being of no cost to families, they have all of the same varieties of foods that are available in other districts across the state and follow all of the same United States Department of Agriculture Guidelines.

“There’s been a move towards less processed food in school lunches, but many schools don’t have the necessary budgets to make lunches healthier,” said Amelia Huelskamp, assistant professor at the School of Health and Applied Human Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. “In the past, the contents of school lunches used to be focused strongly on processed food and meats such as poultry and pork. There’s been some upset from parents because schools are moving away from more of these ‘traditional’ foods.”

While many parents are upset that their children will not receive the same school lunches that they were used to because of more stringent nutrition standards, data shows even more parents are worried about their children not receiving any lunch at all.

Child Nutrition Assistant Elena Alcanter serves lunch to high school students at Blue Ridge School in Cashiers. All students at Blue Ridge School eat free as a part of the federal Community Eligibility Provision program.

March for Our Lives: Students organize march against gun violence

One high school student addresses a crowd of thousands at Martin Luther King Jr. Park in downtown Asheville. Through tears she reads the names of the victims of the school shooting she survived.

Student protesters carry 17 candles to commemorate the people who died in the Parkland shooting during a march on College St. March 25. The crowd of thousands makes up March for Our Lives Asheville, a sister march to the larger movement by the same name occurring the same day in Washington D.C., as well as in other cities across the country. The march responds to the mass shooting which took place at a high school in Florida Feb. 14.

The student, Anna Dittman of Parkland, Florida, is a junior at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where a mass shooting claimed the lives of 17 students and staff in mid-February.

“I remember running away from the school terrified as my classmates jumped over the fence to get away from the gunfire,” Dittman said. “I eventually found my sister and we hugged and held each other, happy that we were safe.”

Dittman spoke Saturday as part of March for Our Lives Asheville, a rally and march set up by local high school students to respond to the shooting in Parkland, raise awareness of stricter gun control laws and advocate for voting into office representatives and officials that support those views.

“After the Parkland shooting, we felt that we could no longer be sitting down. We had to rise up and say what we felt about this issue,” said Aryelle Jacobsen, a senior from A.C. Reynolds High School and one of the student organizers of the event. “We felt like there's such a power to bring our community together and discuss a big prevalent issue and so it was just really gathering together with the students and knowing that enough is enough.”

The march coincided with the larger March for Our Lives event which occured in Washington, D.C. the same day.

“We were ready to stand up and say something. We were ready to stand up and march. My friends were ready to go up to Washington and stand for what we believe in,” Dittman said. “And it's all of us. And with you guys joining it's become a much bigger thing. We're ready for that.”

The march started in Pack Square Park, travelled east along College St. and then south down Martin Luther King Jr. Dr., where it culminated at Martin Luther King Jr. Park. The march attracted thousands of students, teachers and supporters.

“I have seen a change in students’ attitudes about guns in school and doing a lot more of saying something if they see something,” said Lindsay Kosmala-Furst, one of the main speakers in the rally and an educator within the Buncombe County School system for the past decade.

Kosmala-Furst said the event emphasized how America can tackle the problem of gun control and can work through their differences to help make schools a safer place for learning.

“I think this march is going to send a message,” said Lauren Cavagnini, a senior from A.C. Reynolds High School. “And since this is a bipartisan march, hopefully it will bring unity and cause a dialog on how we need to start having these common-sense gun laws in our schools and our communities.”

Tents set up in the park gave supporters the chance to speak with local community advocates, with one tent set up so supporters could easily register to vote. Dakota Sipe, a sophomore from Brevard High School, registered to vote for the first time in his life and cited issues like gun control as reasons for his registration.

“I wanted to support the movement of banning weapons of that are easily accessible to the general population,” Sipe said.

Jacobsen stressed the fight for safe schools is not close to over. She said people can incite change quickly and effectively through voting in officials who will support stricter gun control.

“I think what this rally is going to do for the Asheville community is to unite us together,” Jacobsen said. “So we can join as one to get more local legislation to make sure there's no more gun violence. There's a local sheriff's election coming up real soon and we want to advocate for people to come out and go vote for that. It’s really important that we move forward with this change.”

March For Our Lives: Photo essay

March For Our Lives

Local students organize to march against gun violence

One high school student addresses a crowd of thousands at Martin Luther King Jr. Park in downtown Asheville. Through tears she reads the names of the victims of the school shooting she survived.

The student, Anna Dittman of Parkland, Florida, is a junior at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where a mass shooting claimed the lives of 17 students and staff in mid-February.

“I remember running away from the school terrified as my classmates jumped over the fence to get away from the gunfire,” Dittman said. “I eventually found my sister and we hugged and held each other, happy that we were safe.”

Dittman spoke Saturday as part of March for Our Lives Asheville, a rally and march set up by local high school students to respond to the shooting in Parkland, raise awareness of stricter gun control laws and advocate for voting into office representatives and officials that support those views.

“After the Parkland shooting, we felt that we could no longer be sitting down. We had to rise up and say what we felt about this issue,” said Aryelle Jacobsen, a senior from A.C. Reynolds High School and one of the student organizers of the event. “We felt like there's such a power to bring our community together and discuss a big prevalent issue and so it was just really gathering together with the students and knowing that enough is enough.”

The march coincided with the larger March for Our Lives event which occured in Washington, D.C. the same day.

“We were ready to stand up and say something. We were ready to stand up and march. My friends were ready to go up to Washington and stand for what we believe in,” Dittman said. “And it's all of us. And with you guys joining it's become a much bigger thing. We're ready for that.”

The march started in Pack Square Park, travelled east along College St. and then south down Martin Luther King Jr. Dr., where it culminated at Martin Luther King Jr. Park. The march attracted thousands of students, teachers and supporters.

“I have seen a change in students’ attitudes about guns in school and doing a lot more of saying something if they see something,” said Lindsay Kosmala-Furst, one of the main speakers in the rally and an educator within the Buncombe County School system for the past decade.

Kosmala-Furst said the event emphasized how America can tackle the problem of gun control and can work through their differences to help make schools a safer place for learning.

“I think this march is going to send a message,” said Lauren Cavagnini, a senior from A.C. Reynolds High School. “And since this is a bipartisan march, hopefully it will bring unity and cause a dialog on how we need to start having these common-sense gun laws in our schools and our communities.”

Tents set up in the park gave supporters the chance to speak with local community advocates, with one tent set up so supporters could easily register to vote. Dakota Sipe, a sophomore from Brevard High School, registered to vote for the first time in his life and cited issues like gun control as reasons for his registration.

“I wanted to support the movement of banning weapons of that are easily accessible to the general population,” Sipe said.

Jacobsen stressed the fight for safe schools is not close to over. She said people can incite change quickly and effectively through voting in officials who will support stricter gun control.

“I think what this rally is going to do for the Asheville community is to unite us together,” Jacobsen said. “So we can join as one to get more local legislation to make sure there's no more gun violence. There's a local sheriff's election coming up real soon and we want to advocate for people to come out and go vote for that. It’s really important that we move forward with this change.”

Page Layout

UNCA v. Liberty: Photo essay

Last-ditch effort

Bulldogs lose to Liberty Flames in Big South semifinals

Despite a hard-fought and hectic last few minutes, the Bulldogs were not able to secure a win in the semifinals of the Big South Tournament.

In the bout during last week’s tournament, held in Kimmel Arena, the Liberty University Flames upset the first-seed Bulldogs 69-64.

The match against Liberty was the Bulldogs’ last hurdle before reaching the championship game of the tournament and a chance to advance to the NCAA Tournament.

In the first period the Bulldogs pulled out a 38-26 lead going into halftime. Liberty came out strong during the second period and fired back to claim the win.

Liberty started the last minute of regulation time with a 62-56 lead. This last minute took over 10 minutes due to constant fouls and subsequent free throws from both teams, drawing outraged cries from the fans and coaches in reaction to the tough game.

Sophomore guard Macio Teague and senior guard Raekwon Miller led the game in field goals, with 19 scored by each.

Along with Miller, three other seniors, Kevin Vannatta, Ahmad Thomas and Alec Wnuk played their last conference game as UNC Asheville Bulldogs.

Demonstrators: Photo essay

Demonstrators spark protest

Street preachers come to UNC Asheville's campus to preach messages about morality and religion.